As we look back on 15 years of ICTJ's work, we recognize that our greatest asset is the people whose knowledge, experience, and dedication made our contribution possible. To celebrate all who have been part of ICTJ’s story over the years, we asked some of our former colleagues to share their reflections and memories of moments that stand out: moments that throw the stakes of our work into sharp relief. In the weeks and months to come we will bring you their stories in Reflections on the Struggle for Justice.

Olivier Kambala wa Kambala, an ICTJ Program Associate from 2005 to 2010, talks about the thirst for justice he saw on a visit to Guinea, and how the political situation rendered quenching it impossible.

| It is near the end of 2007, and I am visiting the city of Kindia in Guinea. I am there with a team to assess whether people have an interest in transitional justice and, if so, what their greatest needs might be. This single visit to a city outside of the capital, Conakry, illustrates the depth of the desire for justice—but I realize that I may have little to offer by way of help.

In Kindia, local civil society leaders gathered one bright morning to talk with me about how transitional justice might be relevant to their own experience. |

The meeting started with me giving an overview of transitional justice, after which I opened the floor for discussion. I anticipated reasoned responses, passionate disagreements, and proposals for the future. Someone stood up and began to speak. “They killed my nephew in the street, while he was pleading with them not to shoot.” Another stood up. “They abducted my neighbor, and he came back with broken bones and welts on his skin.” These were stories from a fresh episode of violence that had taken place earlier that year. Soldiers had terrorized the city, murdering people, detaining and torturing protesters, and destroying property. The violence seemed to have touched every family.

More and more people spoke, their voices breaking, their faces contorted with anger and pain. The stories undammed an emotional flood, and everyone in the room struggled to stay afloat. These warm, impressive dignitaries, so composed when we began, were awash in tears.

None of us knew what to do. I adjourned the meeting for half an hour. We walked out of the room into the afternoon sun, allowing the warm light to dry our tears and calm our emotions.

I made the decision to end the meeting early. It occurred to me that this might be the first time people were able to talk openly about what had happened to them. But I had not brought any psychological support to help. I was also concerned that discussion about the past might still be dangerous. Military authorities were still in power, and they were everywhere.

The sun now dimming in the west, my team and I got back into our car and drove back to Conakry, our spirits low.

I recall the ache in the voices of those in that small room in Kindia with deep regret. I tried to follow up a year later, but a new military coup had put an end to whatever political space may have existed during my visit.

10 years since my trip to Kindia, the country is still struggling to implement an institution to establish the truth, provide psychological reparations to the people, and perhaps lay the foundations of non-repetition by exposing past atrocities and building a collective reject of such acts. The raw anger and pain I saw that day lingered with me; yet so too did the readiness to grapple with the past. I always feel indebted to the people of Kindia for having shared their sorrow and hope with me.

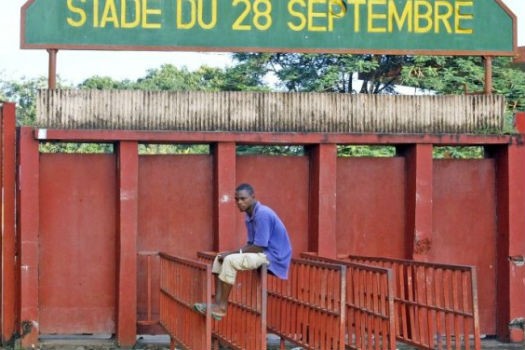

PHOTO: On September 28, 2009, hundreds were killed in this stadium in Conakry, Guinea. The recurrence of violence following Olivier’s visit closed the political space to undertake transitional justice work. (Nancy Palus/IRIN)