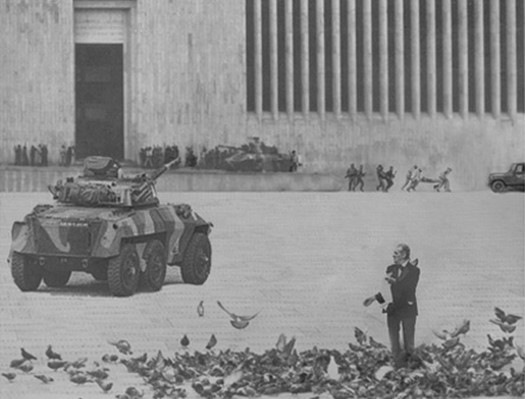

It has been nearly 30 years since one of the darkest episodes in Colombia’s recent history: in November of 1985, M-19 guerrillas occupied Colombia’s Palace of Justice, causing a 48-hour stand-off with the Colombian military, who eventually stormed the Palace to drive the guerillas out. At the end of the siege, one hundred people died and 12 more were disappeared.

Late last year, the families of those disappeared managed to take a step forward in their long struggle to obtain some measure of justice: the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (ICHR) issued a ruling condemning the Colombian state for responsibility in the disappearance of 12 individuals. The whereabouts of 11 of the victims are still unknown.

The 212-page ICHR ruling states that there was a proven “modus operandi” leading to enforced disappearance of persons suspected of having participated in the takeover of the Palace of Justice or of collaborating with M-19. The Court urges the Colombian state to “carry out within a reasonable period of time the broad, systematic and detailed investigations necessary to establish the truth of the events.”

The Colombia case reached the ICHR due to the efforts of relatives of those disappeared during the 1985 siege, after Colombian judiciary failed to conduct its own investigation into the disappearances. While Colombia did convict colonel Alfonso Plazas Vega, who led the retaking of the palace, it never established who was responsible for the 12 disappearances. Now, there is hope that the ICHR ruling will force Colombia to carry out an investigation.

“The ICHR ruling is one more step towards obtaining justice, but unfortunately there is still a long way to go. The victims will only feel that justice has been done when they know for sure what happened to their loved ones and where their remains are located,” said María Camila Moreno, head of ICTJ’s office in Colombia.

“The events of the 1985 siege remind us that enforced disappearance is one of the great omissions in Colombia’s truth-seeking process. This ruling reiterates the urgent need for the state and society to take the necessary measures to settle a historical debt to the thousands of victims of forced disappearance and their relatives in Colombia, and to guarantee that this awful crime be eradicated once and for all from the present and the future of the country,” said Moreno.

In Search of the Truth

Prior to the ICHR ruling, the details of the 1985 siege of the Justice Palace had been the focus of the Truth Commission on the Events of the Palace of Justice. Created in 2005 as part of the efforts of the judicial branch—also a “victim” of the events—the Commission was headed by three former presidents of the Supreme Court of Justice, who were selected to lead the investigation. Their final report, published in 2005, served as a major first step for the country to unveil the truth about the siege.

“The ICHR ruling is based at various points on investigations carried out by the Truth Commission on the Events at the Palace of Justice, and certain sections quote the Commission’s final report,” Moreno adds. “The truth commission contributed to clarifying what happened, and to the ongoing struggle of relatives to assert their right to truth, justice, and reparation.”

However, this Commission was an unofficial truth commission—not formerly established by the government—a factor that caused the ICHR ruling to recognize that “its conclusions have not been accepted by the different state agencies who should be carrying out its recommendations” and, in particular, that a report like that of the Truth Commission “is important, although complementary, [and it] does not override the state’s obligation to establish the truth through the courts.”

“The case of the Palace of Justice is an individual example of the difficulties, but also of the opportunities for cooperation to move forward in seeking the truth,” says Eduardo González Cueva, head of ICTJ’s Truth and Memory program. “Now that Colombia is discussing the possibility of peace and the search for truth on a national level, we should be drawing lessons from this experience: truth-seeking is a task to which both official bodies and society can and must contribute.”

Among various reparations measures, the ICHR ruling orders the Colombian state to provide student grants to relatives of the victims, create a book recounting the victims’ lives, establish a museum or exhibit in honor of their memory, set up a psychosocial assistance program for relatives of the disappeared, publicize the conclusions of the Truth Commission’s final report and the decisions of Colombian courts, and to arrange for a permanent exhibit in the National Museum so that Colombian society may learn about what happened.

Remembering La Toma

In an effort to contribute to honor the memory of the disappeared in the Palace of Justice, ICTJ produced the documentary “La Toma” (The Siege) in 2011. With unedited footage and meticulously reconstructed radio and television archival material, the film takes the spectator through the 27 hours of the occupation and retaking of the Palace of Justice. It then presents the nerve-racking progress of the trial against Colonel Plazas Vega for the forced disappearance of 12 people, mostly cafeteria workers at the palace. The story of the trial is told from different points of view, ranging from that of the colonel himself to the relatives of the disappeared.

Watch the Film