Armenia’s renewed conflict with Azerbaijan has not only attracted the international spotlight, as of late it has narrowed the country’s public policy agenda to issues related to the emerging humanitarian crisis caused by the blockade of the Lachin corridor and peace talks with Azerbaijan. Meanwhile, however, Armenia has been pursuing a range of transitional justice initiatives alongside other democratic reforms for the past five years, and it has made some limited headway, despite setbacks and major challenges.

Five years ago, in August 2018, to mark his 100 days in office, Armenian Prime Minister Pashinyan addressed a large rally in Yerevan’s Republic Square to officially announce his government’s intentions to incorporate transitional justice mechanisms into Armenian post-revolution reform agenda. In his speech, the former journalist and opposition legislator who led the country’s peaceful revolution earlier that year said, “it’s crucial for us to . . . make a decision on the establishment of transitional justice bodies . . . The transitional justice authority is a well-known and generally accepted practice in civilized societies . . . and the international community welcomes this practice.”

Similar to other popular uprisings in the region, Armenia’s 2018 revolution was driven by decades of hardship and abuses—from post-Soviet economic disarray and stagnation to large-scale corruption, election fraud, and human rights abuses carried out by a network of oligarchs and ruling-party politicians that captured the state. Different from those in some neighboring countries, Armenia’s post-revolutionary government, in its early days, indicated a real eagerness to pursue an ambitious and comprehensive transitional justice agenda to address past abuses, seek the truth, acknowledge and redress victims, and pursue accountability.

ICTJ has had the privilege to be among the organizations supporting this initiative. In July 2018, ICTJ experts met with Prime Minister Pashinyan, and, in late 2019, ICTJ established an Armenia country program, which focuses on providing comparative knowledge and technical assistance to policymakers, civil society partners, youth groups, and victims of human rights abuses and corruption.

Unfortunately, since Prime Minister Pashinyan declared his government’s commitment to transitional justice, the country has grappled with a global health crisis, war, and economic uncertainty. These challenges have most certainly diverted attention and resources away from the Armenia’s transitional justice process, but they have not entirely derailed it either.

To date, Pashinyan’s government has yet to implement any transitional justice policies, nor has it adopted a comprehensive transitional justice agenda. No significant measures have been taken to acknowledge and address the demands of families of victims of systemic corruption and human rights violations committed before the revolution who are seeking truth, reparation, and accountability.

That said, the post-revolutionary government has taken some major steps toward justice, accountability, and reform. It has filed criminal cases of corruption and violations of the constitution against former high-ranking officials including two former presidents and their families. It has pressured high-ranking members of the judiciary to resign and opened debate on judicial vetting in parliament, as part of a broader set of proposed judicial reforms. The government has created new agencies to investigate corruption and recover ill-gotten assets. It has also issued official apologies for past violations and held commemoration events, although no truth-seeking body has been established.

The opposition’s autocratic public policy priorities and slogans have yet to gain traction in mainstream politics, even in the wake of the war with Azerbaijan, attesting to the resiliency of democratic ideals in post-revolutionary Armenia. Moreover, a majority of Armenians voted for Pashinyan’s ruling party in two post-2018 snap elections, demonstrating their support for the government’s reforms. And among anti-corruption and human rights activists and youth victims’ groups, there remains broad consensus about the need for comprehensive and systematic change.

Still, enthusiasm for reform has waned considerably in recent years. Many Armenians have grown frustrated by the government’s seeming inaction and are no longer confident it will implement the reforms and transitional justice system it promised. It is thus crucially important to build on the modest gains that been made over the last five years; reinvigorate transitional justice initiatives; and strengthen the capacity of civil society organizations, youth and victims’ groups, as well as the newly established anti-corruption institutions. In doing so, the county will ensure the continued success of its democratic transition, while preventing a recurrence of violence and repression.

__________

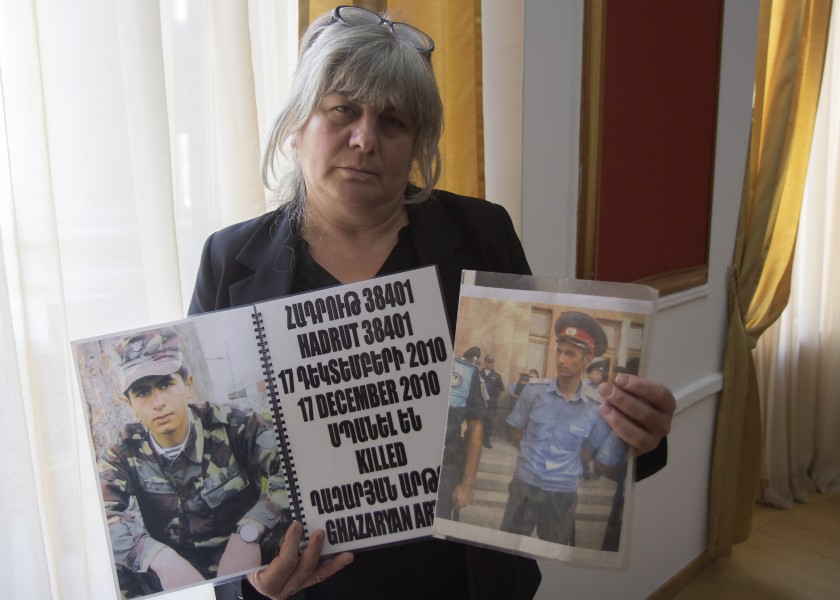

PHOTO: "When the revolution happened, and the [judicial] cases were re-opened, I went to the tomb where my son was buried, and said [to him] it seems there is a door for justice, it seems they could not keep justice away from us,” said Irina Ghazaryan in a 2019 interview with ICTJ. Ghazaryan is a member of Mothers in Black, a group of families that, for decades, have sought the truth about and justice for their sons’ deaths in the Armenian army in non-combatant circumstances. (Diana Alsip/ICTJ)