Ensuring the well-being of victims has long been a core element of transitional justice initiatives. More recently, however, policymakers at the global level have begun to recognize the central importance of mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) in societies emerging from conflict or repression, particularly for victims of human rights abuses. This welcomed and positive development presents an opportunity for transitional justice practitioners to reflect more deeply on what it means to apply a psychosocial lens to their practices and what steps must be taken to meaningfully mainstream MHPSS in the field.

As practitioners have learned from their efforts to mainstream gender issues, it takes more than adding services; it is not simply a matter of bringing in a psychologist. Rather, mainstreaming MHPSS calls for a more deliberate and consistent focus on advancing psychosocial well-being at the individual, societal, and institutional levels at every stage of a transitional justice process, including, crucially, in the overall framing and analysis of the specific context.

ICTJ advocates for the inclusion of MHPSS in all transitional justice initiatives and undertakes research on best practices for the field. Leading this work is ICTJ Senior Expert Virginie Ladisch. She is the lead author of the forthcoming report, 'The Search for People’s Well-Being’: Mainstreaming a Psychosocial Approach to Transitional Justice. ICTJ Communications intern Emma Abdallah recently sat down with Ladisch to discuss the importance of MHPSS for transitional justice and her work on the topic.

Emma Abdallah: What is the role of MHPSS, and how does it help advance the goals of transitional justice processes?

Virginie Ladisch: I think central to the idea of transitional justice is taking a victim-centered approach and doing no harm. And although that's been a long-standing part of our work, more recently there's increased awareness of the interconnection between mental health, psychosocial support, and transitional justice—as a way of promoting well-being at the individual, community, and institutional levels. Some people think of MHPSS as limited to individual support or counseling. While that is an important element, MHPSS is another lens of analysis that we should apply to understand the contexts where we work, for example, by asking: What are the historical violations that took place? What are the specific ways in which that context deals with difficulties? And what are the legacies and the scars of those forms of violence and repression? That helps us to both assess the harms and then think about appropriate responses. MHPSS is not an add-on, but another layer to deepen our understanding of a context and have that understanding shape our response to that context.

Emma Abdallah: How has ICTJ incorporated MHPSS in its work? What are some examples of ICTJ undertaking MHPSS activities?

Virginie Ladisch: It's something that we all do all the time, but maybe we don't call it that. In interviewing our colleagues, we realized that although there's a lot already being done, it’s important to make this focus more explicit and improve our work in this area.

I can give you a few different examples. In Northern Uganda, if we're speaking with a group of women survivors of the war, instead of having one of our Ugandan colleagues—who hasn’t lived through the same difficulty—facilitate the conversation, we develop partnerships with groups of women survivors of the specific conflict who are also community leaders. That way we have people who've been through the experience themselves facilitating the conversation, instead of parachuting someone from the outside who’s a psychologist trained outside of the context. And we also support and tap into already established local networks, which are more sustainable and ensure a more sensitive approach.

Now in Colombia for example, there's the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, which ICTJ has been involved in. In this judicial process set up to try serious cases from the civil war in Colombia, we've been working with psychosocial experts to develop psycho-legal approaches, which help victims and survivors participate in the judicial process in a way that advances their own process of healing and recovery.

These examples show the breadth of what integrating MHPSS looks like in more localized civil society work, as well as in formal, state-sponsored transitional justice institutions.

Emma Abdallah: What are some of the common misconceptions and concerns about MHPSS, both among victims and practitioners?

Virginie Ladisch: I think one of the first challenges is the idea that MHPSS is only about providing support to victims and witnesses, through counseling or therapy. Even though that’s a huge part of it, it's crucial to also connect the individual to their social context—their family, their immediate community, and their larger social community. In the end, our well-being is impacted by events that happen at the national and local levels. And so, one of the first challenges is pushing beyond the limited understanding of this as just support to victims in one very specific form, and that it's not just about dealing with pathologies like severe mental illness. But another challenge is also the stigma associated with mental health. It’s crucial to overcome that stigma. I do think that in the past few years, with the pandemic and forced isolation, there’s been an increase in awareness toward mental health as something that everyone experiences and needs to care for. While I think there's been a lot of progress to break through the stigma, there are still places where that's not the case, including among practitioners.

Emma Abdallah: Based on your experience working with victims, youth, and victims of SGBV [sexual and gender-based violence] in particular, what do you think are the major challenges to incorporating MHPSS approaches or initiatives in transitional justice processes?

Virginie Ladisch: There are several challenges. Specifically, around cases of SGBV—given the stigma that exists—it's important to be able to provide support that doesn't expose victims or survivors to further stigma. This is key, especially if they haven't revealed to their family, or their community, that they were a victim of SGBV. We have to be very careful. It’s also important to be sensitive to what is culturally accepted in a specific context. If we want to have a consultation with women survivors, we're not calling it, for example, “consultation on what victims of SGBV want as reparations.” We would instead use terms that relate to the context but that would not put victims and survivors at risk such as “women in peacebuilding.”

Another huge challenge is that this work is very long-term. There's no quick fix, so it requires a long-term approach to address the harms at all levels and push for the transformation of norms, so that violence doesn’t get normalized. So, it's also about how to establish new ways of interacting and relating individually and with the state. It's a long-term process that requires a long-term investment, both in terms of time and resources, and flexibility.

Emma Abdallah: Cultural practices and beliefs, particularly in relation to victimization and mental health problems, can heavily influence how victims and practitioners view MHPSS. What challenges do these practices and beliefs pose and how significant are they? How can MHPPS initiatives address these challenges, such as stigma?

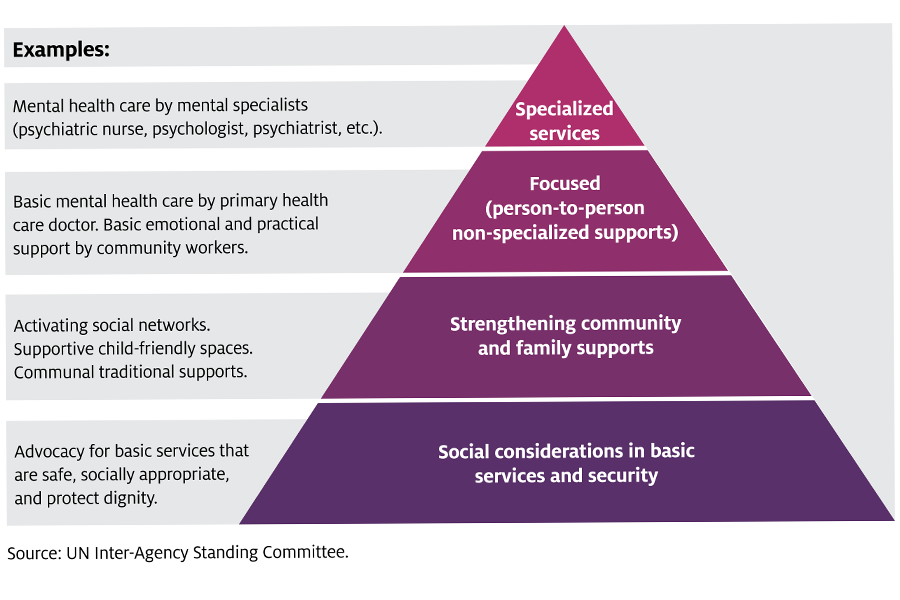

Virginie Ladisch: The term “mental health” in itself can sometimes bring a lot of stigma. Adding the psychosocial framing is key, since it tends to carry less stigma. In general, though, in each context, certain terms are more commonly used than others to refer to dealing with difficult emotions or grieving. So, it’s important to be context-specific and culturally sensitive and work with trusted leaders within the community, who don’t necessarily have to be trained psychologists or therapists. The pyramid of care [Figure 1] highlights that, for the majority of the population—the base of the pyramid—support can be provided by local trusted leaders [and] support workers. In rare cases of severe mental illness or psychological conditions—the top of the pyramid—there is a need for trained specialists. Generally, the work we do at ICTJ is focused on the base of the pyramid, which is embedded within the community, which both helps you reach more people and helps combat stigma and resistance to psychosocial support.

Figure 1: UN Inter-Agency Standing Committee’s Pyramid of Care

Emma Abdallah: MHPSS is most often thought of in relation to victims, even at times perpetrators. But, what about practitioners and other frontline workers and activists? What are their MHPSS needs? Should initiatives be designed for them, and if so, how?

Virginie Ladisch: This is hugely important. Brenda Reynolds—a social worker from Canada who designed and led the mental health and psychosocial supports for the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission—noted that when truth commissioners and staff were offered support and care, some were initially resistant to it. But, she helped them see that eventually the stress will catch up with them and get in the way of their work. On this, she said: “You can't take a survivor any farther than you have not walked.” It’s crucial to remind ourselves that, if you are not taking care of your well-being, you can’t accompany victims and survivors in that journey. There's also a risk of having a bit of a savior or martyr mentality or a level of guilt with practitioners because they feel they have it easier than the victims they’re helping. But secondary trauma is very real. Another clinical psychologist, Nomfundo Mogapi—former head of CSVR [Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation] in South Africa, now heading her own organization called the Center for Mental Wellness and Leadership—refers to trauma as a hazard of the profession. She talks about staff welfare and staff care as a necessary tool of the job; just as you give someone a laptop, you need to support their well-being. So, just like MHPSS in transitional justice, Mogapi emphasizes, staff welfare can't just be this side issue, but needs to be built into how we do our work and supported by senior management, the board, and donors.

Emma Abdallah: In the years to come, what changes or improvements would you like to see in the transitional justice field with respect to MHPSS?

Virginie Ladisch: Just as we mainstreamed gender throughout our work several years ago, we must do the same with the mental health and psychosocial lens: Integrate this analysis and new set of questions to fully understand contexts and make sure our work takes a trauma-informed approach at all stages and all levels.

It’s also crucial to build partnerships with those who are engaged in this work and have expertise in psychosocial support, mental health, and different therapeutic approaches. We can't accomplish TJ without MHPSS and MHPSS can’t happen without TJ, because oftentimes the drivers of injustice that affect people's well-being negatively are also the drivers of injustice that we're seeking to address through TJ processes. So, I would really like to see us continuing to build those partnerships and also to improve our work around caring for the caretakers. That's fundamental.

Emma Abdallah: What is ICTJ doing now or intending to do in the near future to better integrate MHPSS in its work and the transitional field more broadly?

Virginie Ladisch: The report on MHPSS that I've just finalized takes stock of what we already know and do and highlights the areas where we may need more support. It’s important to uplift what's already been done but to then also find ways to deepen the work where we’ve noticed some gaps. Going forward, I also hope that we can put together a working group with other organizations with psychosocial expertise to keep building those partnerships and referral networks, which will be crucial to successfully mainstream a psychosocial approach throughout our work. We've also already started integrating a focus on MHPSS internally, for example at our last staff retreat, and in the work we do with our beneficiaries, for example, by partnering with the Center for Victims of Torture to codesign and cofacilitate our workshops. We are also bringing this topic to global policy discussions, such as the recent AU-EU expert seminar where MHPSS and TJ were some of the key topics explored.

But this is only the beginning. We're going to keep learning, building on what we've done, and deepening it.

Emma Abdallah: Thank you so much, for all the information, for everything. It's been a real pleasure.

Virginie Ladisch: Thank you for putting together the questions. It's been great to speak with you.

______________

PHOTO: A victim alongside her psychosocial support provider listen to former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) commander, Rodrigo Londoño, ahead of the first acknowledgment hearing of Colombia's Special Jurisdiction for Peace in Bogotá in June, 2022. (Maria Margarita Rivera/ICTJ)